A STORY BY KARI MUGO, FEATURING ART BY DYANI WHITE HAWK, WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY ANDRES GUZMAN.

Melissa Olson’s discovery, two years into her PhD program in American studies, was one that would alter her life’s course. Enrolled in the University of Minnesota Twin Cities and a MacArthur Fellow at the time, Melissa attended a talk by writer and Korean transracial adoptee Kim Park Gregg. Afterwards, as her and a friend stood outside talking, Melissa’s friend mentioned the Indian Adoption Project. This would be the first time Melissa would hear about the policy that had dramatically changed her family’s life.

She was speechless.

M E L I S S A O L S O N

“You’re telling me this thing I’ve lived all these years has a history and that history includes some policy and that policy has been unknown to me? I’m a second year PhD student. To be at that level of study and for that to just be known, it still floors me.”

“You’re telling me this thing I’ve lived all these years has a history and that history includes some policy and that policy has been unknown to me? I’m a second year PhD student. To be at that level of study and for that to just be known, it still floors me.”

The Indian Adoption Project (IAP), which resulted in the out-of-home placement of many Native American children, lasted from 1958 through 1967. It emerged during the U.S. federal government’s ‘Termination Policy’ that sought to assimilate Native tribes into the larger American fabric “as rapidly as possible.” This meant removal of federal protection of tribes and tribal lands and the transfer of civil and criminal jurisdiction to the states, affecting laws around “social services, child welfare, probate, those kinds of civil matters,” Melissa says.

“There was a big effort to either remove Native kids from their homes and adopt them, or make them available for adoption. My mom is part of that generation.”

“There was a big effort to either remove Native kids from their homes and adopt them, or make them available for adoption. My mom is part of that generation.”

![]()

Melissa’s mother was two years old when her and her siblings were taken from their mother and placed in what was then St. Joseph’s Orphanage (now St. Joseph’s Home for Children). Not much is known of the exact circumstances that led to their removal. Melissa’s mother would end up in at least two other foster homes before a white family in New Ulm adopted her at the age of seven. Leaving New Ulm as an adult, she moved around the country before settling in Minneapolis in the early 90s. She was able to reconnect with her biological siblings and Melissa grew up cradled between these two sets of families and cultures.

“I grew up with my mom’s adoptive family and my mom’s biological family. That was normal to me, although it wasn’t necessarily the experience of everybody else.”

One of the reasons why Melissa may not have considered her upbringing any different is because of the number of transracial adoptees in her mother’s generation. Findings from an Association on American Indian Affairs report showed that “eighty-five percent of the Native children removed from their families from 1941 to 1967 were placed in non-Indian homes or institutions.” Run by the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA), the IAP was funded by the United States Children’s Bureau and the Bureau of Indian Affairs to help remove barriers to legal adoption of Native children by non-Native families since tribes were sovereign states. This act of goodwill was coded in the racist ideology that white families could better care for Native children.

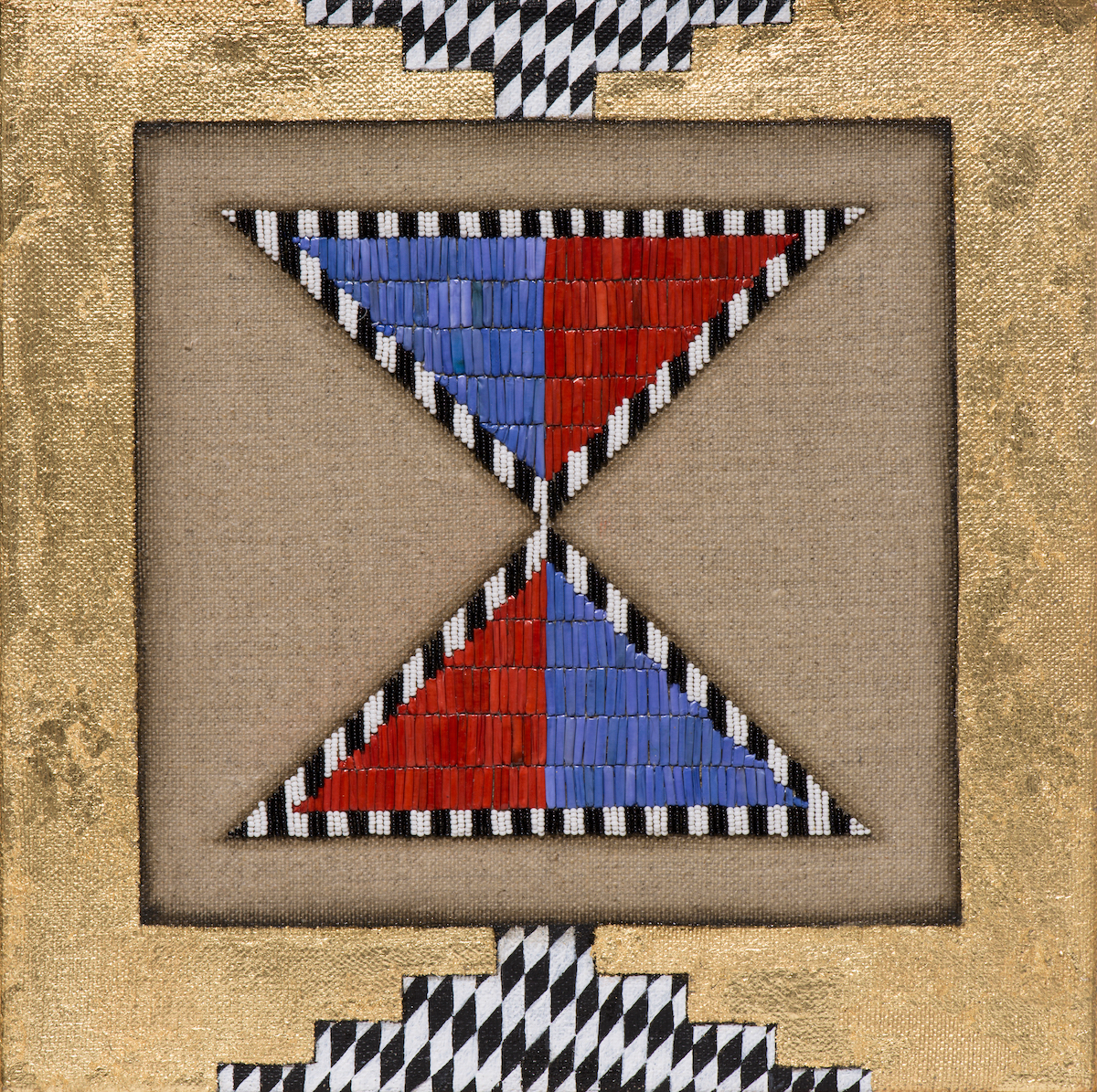

Understanding – Dyani White Hawk

JUDY OLSON (MELISSA’S MOTHER)

The results were traumatic for Native tribes; children could be removed from their homes more easily, families were broken up, and transracial adoptees had to contend with growing up in communities and cultures other than their own.

“As she grew up she experienced a lot of different kinds of racism, of otherness, I guess you would say,” Melissa says of her mother.

“As she grew up she experienced a lot of different kinds of racism, of otherness, I guess you would say,” Melissa says of her mother.

As Melissa grappled with what the history of the IAP meant for her personally, she was also dealing with its academic erasure. As she searched for more information on the project locally, she could locate few primary documents.

“The bigger story was there really was nothing about the history of transracial adoption.”

Armed with what she calls the “intellectual voracity” of graduate school, she poured over papers at the University of Minnesota’s Social Welfare History Archive, housed in the Elmer L. Andersen Library. When this wasn’t enough, she ventured into the Minnesota Historical Society’s (MHS) archives. She got a hit on MHS’s search engine one night.

“The citation looked like one document said ‘pamphlet in the papers of Elmer L. Andersen.’ I didn’t realize the connection to [the Elmer L. Andersen Library] at the time.”

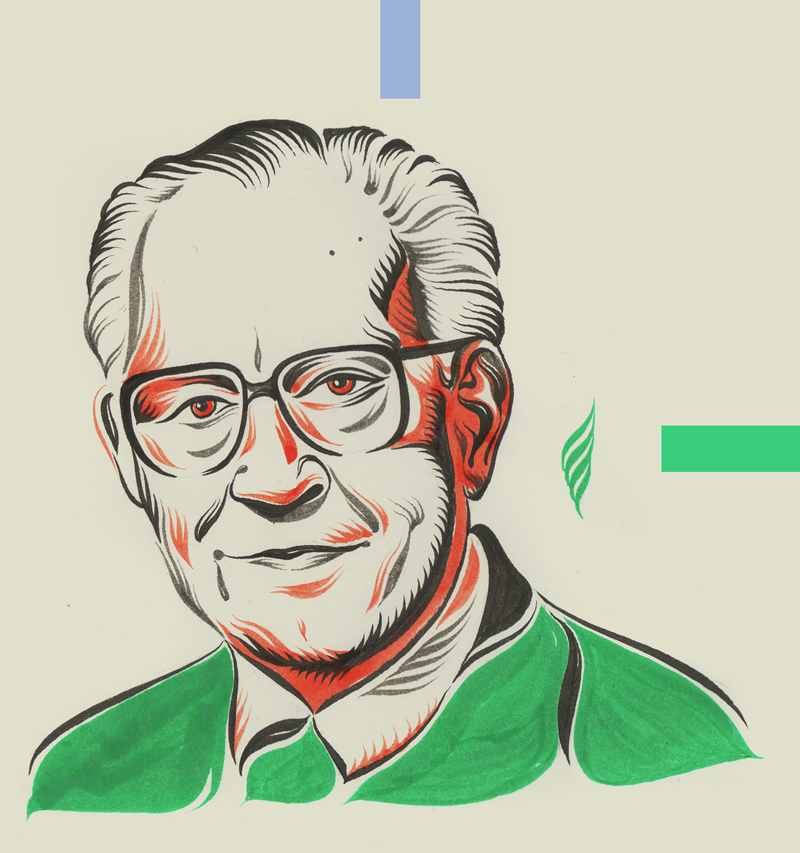

Visiting the archive the next day, Melissa found four boxes of materials relating to the Indian Adoption Project and Elmer L. Andersen’s work with the CWLA. A one-term Minnesota governor from 1961 to 1963, Andersen sat on the board of the CWLA and was intimately involved in the IAP locally. In Andersen’s MHS archives, Melissa found minutes of CWLA board meetings, budgets, and correspondence letters detailing some of his work. Andersen, whose name is also honored in the Elmer L. Andersen Human Services Building by the Minnesota Department of Human Services, was recast as a villain in Melissa’s eyes. Yet here he stood, celebrated as a social welfare hero in state and public institutions.

ELMER L. ANDERSEN

“He was what we think of as a ‘compassionate conservative.’ I think he cared about children but that whole idea was so misplaced and rooted in colonial politics. Other universities, other places have gone through some of these discussions around what kind of power is in naming and we need to have that discussion around this issue.”

“He was what we think of as a ‘compassionate conservative.’ I think he cared about children but that whole idea was so misplaced and rooted in colonial politics. Other universities, other places have gone through some of these discussions around what kind of power is in naming and we need to have that discussion around this issue.”

For Melissa, Andersen and the IAP’s legacies go far beyond the decade of official policy that led to the transracial adoption of 395 Native American children through the CWLA. Melissa notes that the 395 figure leaves out adoptions carried out by organizations other than CWLA. The project was only one model of many, and it played a major role in illustrating how transracial Native adoptions could be carried out in various settings and through other child welfare organizations. It is estimated that during the “Adoption Era” of 1941-1978, as many as 25 to 35 percent of all Native children were displaced from their families through similar programs. Likewise, Melissa asserts that the effects of the IAP linger on even after the 1978 passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act that made it harder to remove Native children from their homes.

“Today, there are still so many American Indian kids displaced from their homes and the rates of American Indian children in out-of-home placement are hugely disproportionate to the number of white children in out-of-home placement.”

Melissa now works in child welfare within Hennepin County. It was here that she struck up a friendship with a co-worker whose mother had also been a transracial adoptee.

“I would say it was the first really in-depth conversation I had with a peer who shared that in common. The gift of that cannot be replaced, it can’t be undone.”![]()

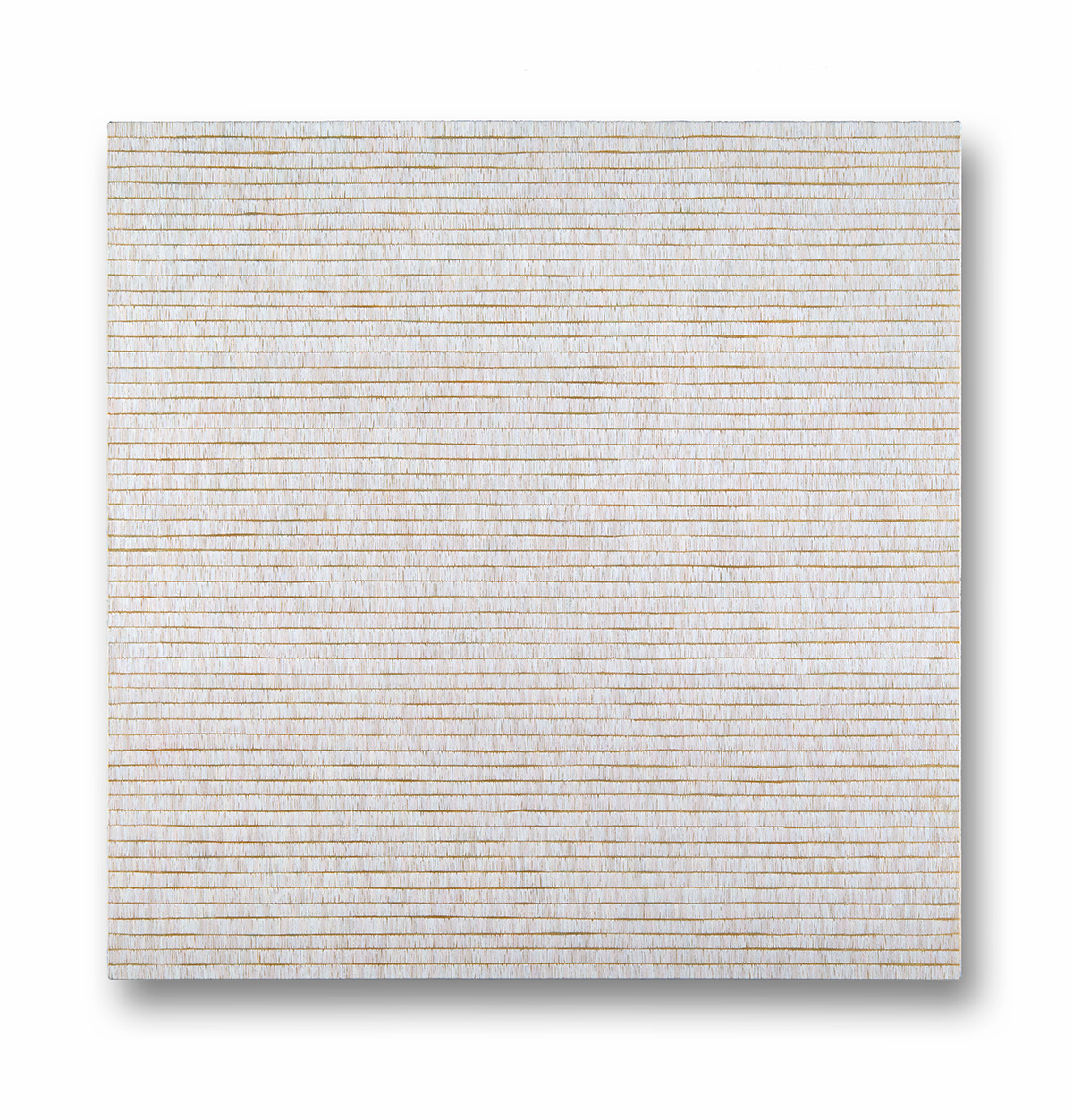

Understanding II – Dyani White Hawk

At around the same time of this initial conversation, Melissa had secured Tiwahe Foundation funding to take part in an indigenous people’s health conference in Winnipeg, Canada. Attending a Tiwahe grantee convening after the conference, she learned of a fellow grantee whose mother was also a transracial adoptee. Melissa was struck by the woman’s story and reached out to see if she would be interested in working on a project exploring the mother-daughter experiences of Native American transracial adoptees. The woman, Melissa Davis, agreed. The women recruited two more women to the project and started planning.

“It started as a way to be selfish and say, ‘I’ve never really sat with another group of folks who have this common thing.’ We had a couple of meetings at a coffee shop and had that conversation over and over.”

![]()

They pitched their project as an audio documentary to the Tiwahe Foundation and received some funding for it. Additional funds were provided by the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community and traditional fundraising. Over the course of a year, the four women set to telling their mothers’ stories through interviews while weaving in history through the voices of experts such as Margaret Jacobs, a historian whose work has explored the Native American experience during the boarding school and adoption eras. The 54-minute audio documentary titled, Stolen Childhoods, wants to begin to heal some of the wounds within the Native community by normalizing these stories.

“It’s been very difficult to discuss that level of child loss in a community that already experiences a lot of child loss and displacement. To normalize that and be able to talk about it so the kinds of issues adoptees have are not surprising to people—whether that’s support in searching for relatives, obtaining legal documents, or the kinds of things that go into reclaiming a part of one’s identity.”

The documentary also wants to counter the institutional erasure of this period of history through storytelling. By documenting and archiving the experiences of their mothers and others like them, the project hopes to create a historical memory that may encourage other adoptees to come forward and share their stories. On a more personal note, this project for Melissa is about the responsibility she feels to tell her mother’s story.

“Her name is Judy,” she says of her mother, “She gave herself her own name at a very young age. That’s one of the things we found, that a lot of adoptees found middle ground by conferring names on themselves. We think that my mom heard Judy Garland on the radio and named herself after that, and she’s been Judy ever since.”

![]()

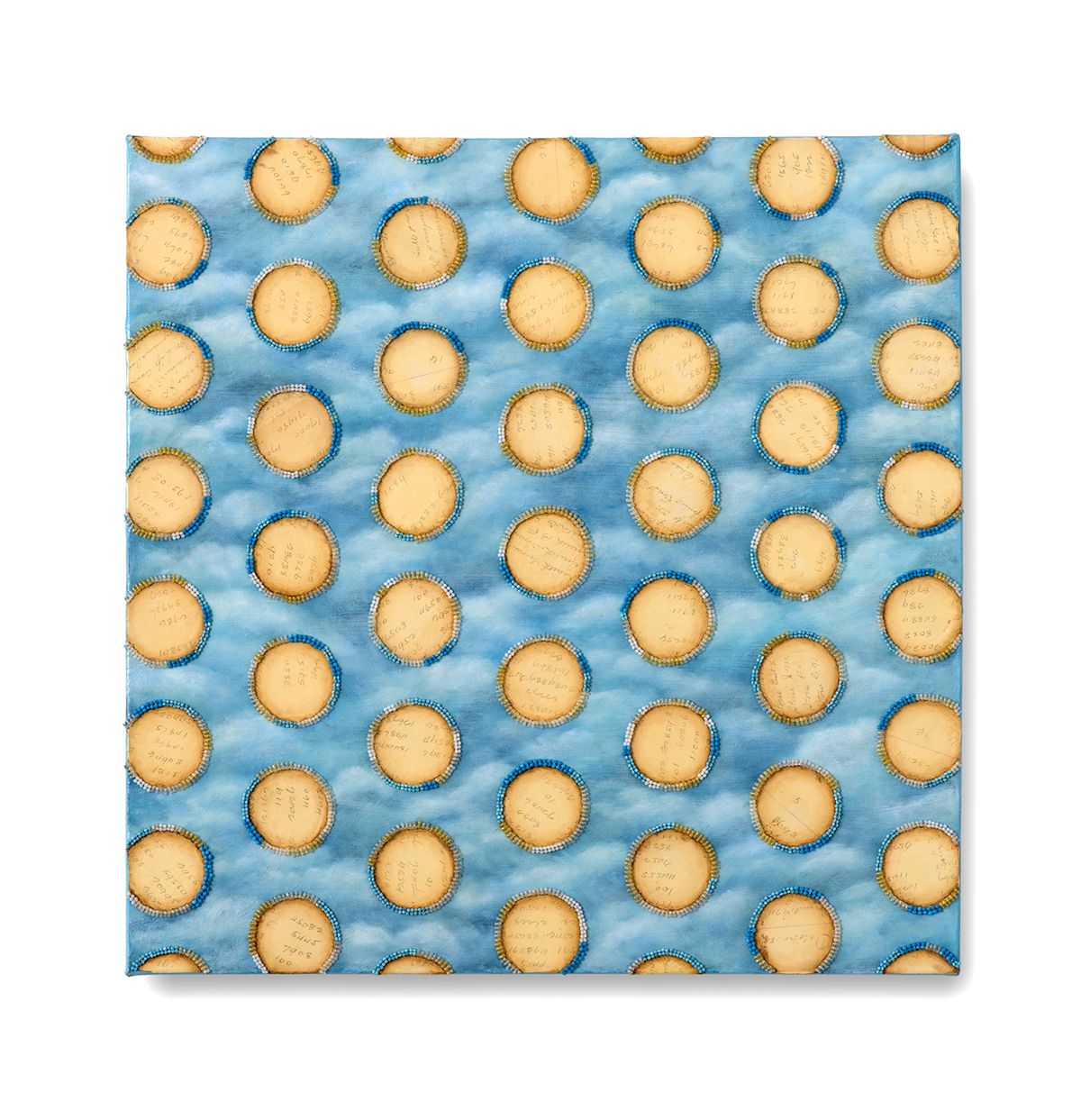

Dragonfly, Sun, Moccasin – Dyani White Hawk

Documentary

Stolen Childhoods, an audio documentary written by Melissa Olson, Ryan Katz, and Todd Melby aired during the Listening Lounge On KFAI 90.3, November 16 at 7pm. And will air on November 21 at 9am on Truth to Tell. You can listen to the podcast below.

To support the project, visit their

GiveMN page.

- Connect with The Tiwahe Foundation. The Tiwahe Foundation was instrumental in making Melissa’s journey possible. Tiwahe invsests in a Circle of Giving—a continuous cycle of success grounded in indigenous culture that recognizes giving benefits both the giver and receiver.

- See Minnesota’s disproportional rates of placing Native American children in foster care in a report from MPR based on 2009 census data.

- Listen to a podcast on “tragic history of Native American children taken from their families” from Radio Lab’s More Perfect.

- Locate resources the United States government offers to separated families.

- Reach out to a support group. Sandy White Hawk leads the First Nations Repatriation Institute, and offers insight, resources, and support.

- Read more on the adoption era:

Contributors

Pollen contributor,

Pollen contributor,