The Ugly Little Potato sat apart from the rest of the spuds at a plant in the Red River Valley. With its small stature and slightly blemished surface, it wasn’t allowed to join the group of pretty potatoes set to ship from the packaging plant to grocery stores later that week. Instead, it sat among the pile of potatoes deemed too large, too small, oddly shaped or too marked up to sit on a dinner plate. These were the rejects. Instead of becoming food, they were set to become trash. That is until GPFB found them.

Steve Sellent, the executive director of GPFB, sent a staff member to tour the facility in 2011. “They said they had no product available to donate. We discovered that millions of pounds of potatoes were being discarded because they didn’t quite meet appearance standards,” said Steve. Although these potatoes were ugly, in most cases, they were edible and nutritious. Instead of heading to the landfill, the little ugly potato and its pile of castoffs were redirected to the doorstep of North Dakota’s only food bank. In its first year, the GPFB’s Potato Recovery Project put 1.1 million pounds of the red-skinned vegetable on dinner tables across the upper Midwest.

But the Red River Valley potato rescue mission was just the start. In a world where Instagram has turned photographing beautiful food into an art, GPFB has been sticking up for the ugly potatoes of the world, turning the recovery of unwanted food into an art of its own. When grocery stores find a bruised apple or gallon of milk set to expire, GPFB swoops in to redirect those valuable resources away from the garbage dump and onto the shelves of its food pantry partners across the state.

For one in 10 North Dakotans, the charitable feeding network has been the difference between having food on the table and going hungry. As the only food bank serving the state of North Dakota and the Native nations that share the same geography, GPFB can’t afford to let any food go to waste.

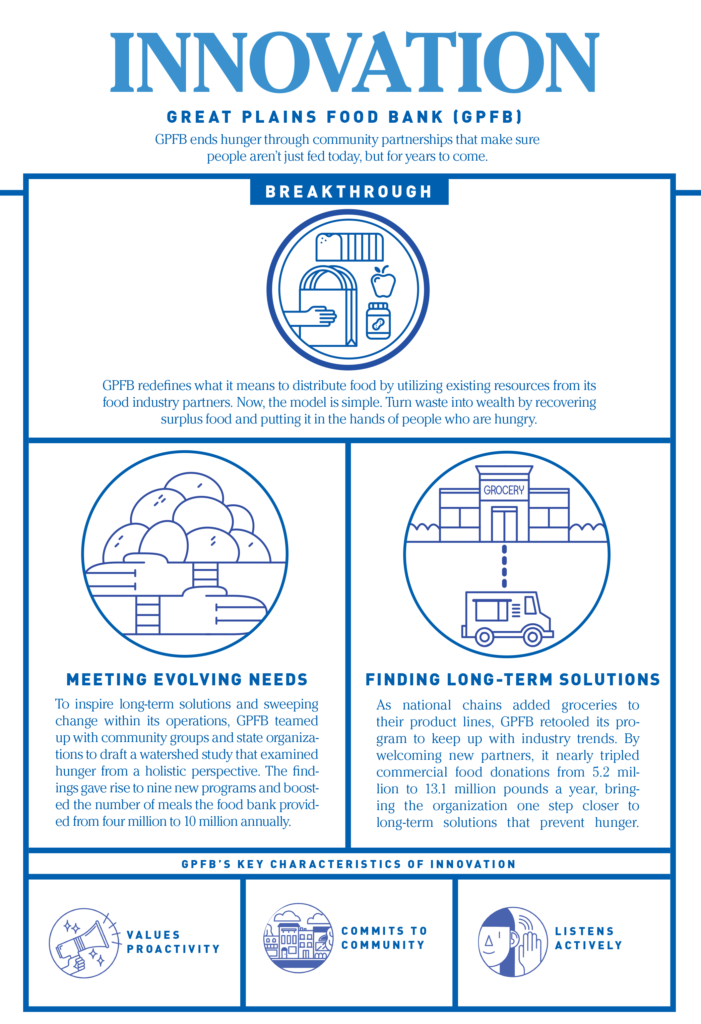

For more than 25 years, the staff at GPFB had faced the real rumblings of hunger head on by putting food on people’s tables. But around 2008, demand started to outgrow resources. When the charitable feeding network couldn’t keep up with changing demographics and trends, GPFB recognized it needed to make a radical shift in the way it operated if it was going to realize its goal of making North Dakota a hunger-free state.

Food banks across the country began shifting their work away from short-term solutions that react to hunger and toward long-term solutions that actually prevent hunger. “We knew we needed to attack the issue of hunger from a new direction while we continued our current work,” Steve said. “Our focus has always just been on getting food on people’s plates, but how do we continue to feed that line while also shortening the line?”

To answer this question, GPFB produced “Create a Hunger-Free North Dakota,” a landmark comprehensive study that hinged on collaboration with partners throughout the state that not only were passionate about hunger relief, but also would offer a fresh approach to the work. GPFB went to one of its board members first and asked Ann Pollert, the executive director at North Dakota Community Action Partnerships, if her organization would team up on the survey. The group agreed. From there, the partnership list grew organically. Community Action leveraged its network to bring the Department of Commerce into the fold, and soon GPFB had locked in four partners throughout the state and across sectors, including the USDA’s Grand Forks Human Nutrition Research Center and North Dakota State University Extension Service.

By bringing together a variety of perspectives, GPFB hoped to piece together a holistic view that wasn’t limited by a single experience or way of working. “We all play a role in North Dakota, but didn’t collaborate to the degree we thought we could,” said Steve. Opportunities to collaborate bloomed once the staff traveled across the country to attend conferences, workshops and sessions. At each stop, GPFB took notes on how individual food banks approached fresh topics such as collective action. They also paid keen attention to the regional food banks tackling long-term solutions to hunger.

The endings from the study inspired nine new programs and increased the number of meals the food bank provided from four million to 10 million annually. The survey also highlighted significant portions of North Dakota going underserved. “As we grew as an organization, we were able to bring in more expertise in terms of staff, board members and stakeholders,” said Steve.

GPFB’s initial goal was to collect 100,000 pounds of food a year from the entire Hornbacher’s Grocery Store chain. Instead, they got 100,000 pounds of food from each store. Local grocery store chains have long been a part of the charitable feeding network. Over the past several years, as national chains added groceries to their product lines, GPFB retooled its program to keep up with industry trends. By welcoming new partners, it nearly tripled commercial food donations from 5.2 million to 13.1 million pounds a year, bringing the organization one step closer to long-term solutions that prevent hunger.

“We had to change along with the food industry if we were going to expand our program,” said Steve. The results have been impressive. A whole bunch of food finally found its purpose in life. In the past, GPFB saw its main role as supplying resources to keep the region’s food pantries and kitchens stocked. Now their solutions are meeting long-term needs.

Produced in partnership with the Bush Foundation

to showcase the culture of innovation

behind its Bush Prize winners.

Contributors