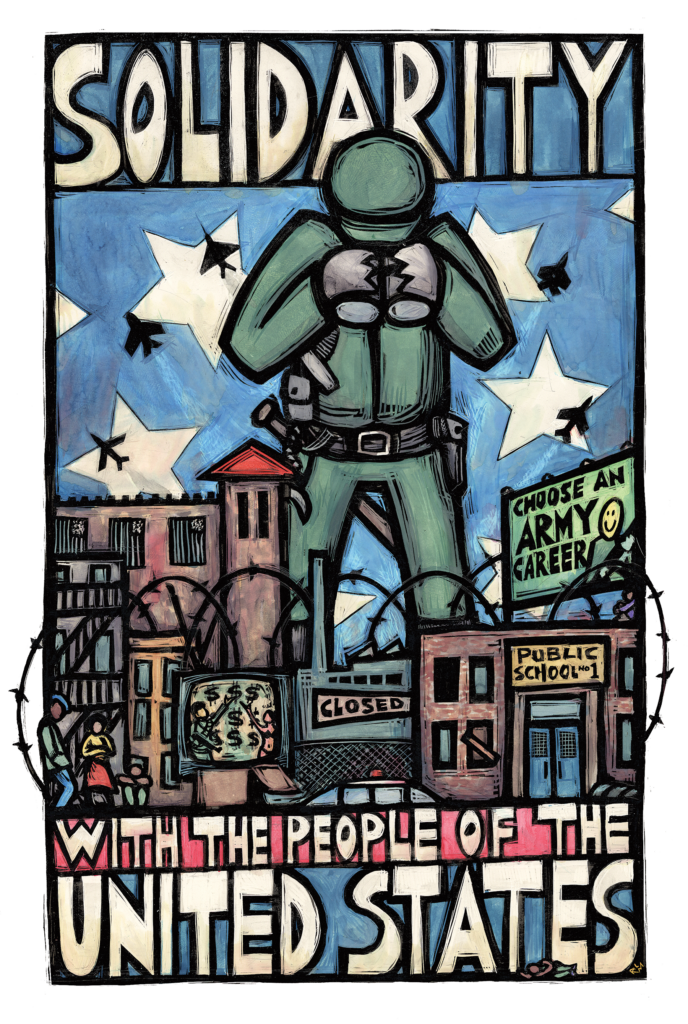

art and story by

Ricardo Levins Morales

I didn’t know much about police until my family moved to Chicago from Puerto Rico in 1967.

They were not a presence in the mountain barrio where I was born. Our town, Maricao, was a forty-five minute drive down winding mountain roads. We collected rainwater for our use and there was only one (usually broken) phone within miles. I didn’t know that governments provided services.

In Chicago cops were everywhere.

Here’s an early memory from then. I’m walking along a street one day and there’s this Black kid around my age walking up the block ahead of me. I hear the purr of a squad car behind me, crawling along. The cop rolls up on the kid and blasts out the loudspeaker “you’d look good behind bars!” then he guns his engine and peels away.

Even with my light skin I’d get harassed. Not like my darker friends, of course. But the sight of young folks of different colors hanging out together? It was like a personal insult to cops. “Why were you guys rattling the grate on that liquor store?” “What are you talking about, man? We didn’t go anywhere near there!” “If I say you did,” explains the cop. “And he says you did.” (Indicating his partner.) “Then you did.” You get used to it.

I learned pretty quickly to keep to the back streets and alleys where I might run into a squad of Blackstone Rangers – or occasionally some Disciples – and avoid the lit up boulevards where the CPD patrolled. The gangs might take your money but they weren’t going to humiliate you. They knew they’d still have to share the streets with you tomorrow so why make an enemy? The police on the other hand could do whatever they felt like, and they didn’t care.

They made the rules. I didn’t know it then, but during my teen years in Chicago, the mighty Blackstone Rangers were careful not to kill any white people (except once in a botched robbery). It was understood that the cops would look the other way as long as the victims were Black. But taking a white life? That was forbidden. You know that “Black-on-Black crime” they’re always talking about? There are police fingerprints all over it!

Fast forward fifty years and not much has changed, despite years of failed reforms. Former LA County sheriff’s assistant chief Neal Tyler compares it to a pendulum. First there’s a police killing or brutality scandal, he says, and everyone’s calling for reform. Then, when there’s an upswing in street violence and community leaders demand protection.

“People start saying, ‘Come on. Beef up the police.’” explains Tyler. “And we do that, and then slowly, eventually, we lose our resolve and the pendulum swings back the other direction and there’s a police scandal of epic proportions. Like clockwork.”

That pendulum doesn’t swing all by itself, though.

In Minneapolis, a group of concerned Northside residents is helping to push it along. Faced with a rash of shootings and beatings in the neighborhood, they sued the city to demand more staffing for the MPD, a department that can barely get itself to stop killing dark people for a single news cycle.

The right-wing law firm that financed their lawsuit also has strong opinions about racial justice. One of its pet hobbies is attacking Black Lives Matter, the 1619 Project and, especially, critical race theory for their “abhorrent, racially divisive ideology, grounded in Marxism and anti-Americanism.”

These neighbors do acknowledge that all is not right with the cops. “We hate the explosion of the prison industrial complex and the disparate incarceration of Black people,” they declared in an op ed. “And we want changes in the entire criminal justic e system that stops, searches, charges, convicts and sentences inequitably at each step. African Americans, especially, desire a relationship with our cops of mutual respect, support and accountability.”

But here’s the thing:

Police are gold-medalists at nullifying reforms, and “mutual respect, support and accountability” with Black communities isn’t high on their agenda.

“At each agency,” reports the Washington Post. “the attempts have been stifled by entrenched cultures, systemic dysfunction, shifts in leadership and swings in public mood.” Case-in-point: A coalition of Minnesota police chiefs, sheriffs’ organizations and police unions are now suing to repeal recently enacted limits on police use of deadly force.

Even as their defenders concede that change is needed, the grip that police have on public resources (they consume over a third of the Minneapolis city budget) and imagination (half of network tv dramas are cop shows) leaves little room for alternatives. Who else can you call about a missing child, a sexual assault or a mental health crisis?

Making that call, in a moment of crisis, is an agonizing decision for people in poor and dark communities. It’s like calling your abuser to protect you from abusive neighbors. All too often it leads to tragedy.

If we’re serious about getting off that pendulum, we need to take a hard look at the origins of modern policing. Following Emancipation the challenge for southern whites was how to keep Black people in servitude post-slavery. Their solution? To make virtually anything a Black person might do illegal (including not having a white employer, “walking without a purpose” and “walking at night”). They could then be swept into the prisons and leased back to plantations. Branded with a lifelong “criminal record,” they’d be denied access to the rights and benefits of citizenship. In other words, pretty much what police still do. But now instead of “Black codes” any law (real or invented) can be applied based on skin color.

Supporters of the police system are right on one key point. A system that sends billionaires on joy rides in space while hungry children sleep in the street really does need a violent paramilitary force to keep “order.”

You cannot solve the problem of policing while ignoring the massive inequality it’s there to protect.

You can’t solve crime on the streets by shoring up the street-to-prison pipeline that just perpetuates poverty and trauma.

Private equity firms snapping up single family homes on the Northside are a real threat to community safety, not protesters demanding an end to police abuse. It will take radical investments in the stability and well-being of young people, their families and neighborhoods along with accountable, community-based intervention and support systems. That’s how we change the message from “you’d look good behind bars!” to “you’d look good behind a telescope!”

That’s how we stop the pendulum!

Contributors