“We can’t all of a sudden get down on our knees and turn everything over to the leadership of the blacks. I believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to the point of responsibility. I don’t believe in giving authority and positions of leadership and judgement to irresponsible people.”

–actor John Wayne in a 1971 Playboy interview

Two years ago, I started work as a recruitment and retention specialist for a small Minnesota nonprofit. The organization’s mission was to serve youth in crisis and their matriculation rate was 90 percent poor Black kids. I was hired on to replace a woman they fired a month prior, a Black woman, for reasons unresolved. She had been telling people that she was pushed out for challenging racist policy. Administration only disclosed she created a hostile work environment for others. Either way, I shelved the information and stepped lightly into my new role.

The administration was starkly white, 90 percent or thereabout, and female. My direct supervisors, two white women in their 40s and 50s, held long tenures in this industry as previous program managers in high ranking leadership positions. They were friends from before and followed each other to this organization after their previous one folded. When I first interviewed for the position, and for every consecutive meeting to follow, they kindly requested that I meet with both of them together.

At first the three of us got along well. They liked me because I took to their mentorship and “fun” managerial style and offered my help to colleagues around the office. When the workload was light, I would be the only one from my department visiting the youth floor to spend down time with the kids and talk about their day. I enjoyed recreation with the kids because it allowed me brief escapes from my desk – nestled narrowly in-between my bosses’ offices – and the white enclave of the administrative wing.

It was six months in, during one of our recurrent check-ins, that our three-way lookingglass began to crack. We were going through reports on recruitment and retention when I noticed an odd trend. Our department had tripled the number of volunteers coming in for weekly shift rotations but incredibly, the entire pool was white. No one had noticed. When I brought it up, and offered to lead an effort to pull in more volunteers of color, the more outspoken of the bosses interjected with, “Well we could look for more Black volunteers but I don’t think they would pass our background check.” I paused for a moment to settle my face. The other boss had not so much as flinched. Confused, I assumed I had misheard and asked Outspoken to repeat herself. She did, and observing my shock, added, “I didn’t say anything wrong. I’m not a racist.”

A 2016 survey conducted by GREATER MSP, the Bush Foundation and the St. Paul Area Chamber of Commerce found that out of more than 1,200 local professionals of color, 16 percent said they were looking to leave Minnesota because of a “lack of diversity and cultural awareness” in the workplace. Among professionals of color under the age of 30, that rate rises to 22 percent. Respondents said that even when their organizations take up diversity and inclusion initiatives—which 71 percent reported was the case—most of those initiatives were ineffective. The reason these statistics exist today is due to a workplace culture of white supremacy.

White supremacy is defined as a system designed to set whiteness as the default for societal norms. This means in white-led and white-dominant organizations, whiteness is the standard for office behavior, workplace values, and the criteria used to discern merit. Because all desirable qualities and skillsets are expected of whiteness, and all pejorative qualities and skillsets are expected of “non-whiteness,” people of color entering into this space inherently exist in tension with the culture. The tone and manner of speech is in tension. Wearing locs, braids, or headwraps is in tension. Heating up food from non-Western countries is in tension. Even taking breaks throughout the day to pray, a protected right, is in tension.

In addition, employees of color who attempt to assimilate to, appease, or perform whiteness automatically lose those conditional privileges once their attempts become inconsistent or futile. White supremacy labels them “insubordinate” and expendable.

“The main problem nowadays is not the folks with the hoods, but the folks dressed in suits,” Duke University professor Eduardo Bonilla-Silva said in an interview with CNN.

The extreme caricatures of white supremacy —John Wayne, KKK, birthers, Tea Party, Breitbart News—are frequently lambasted, but how many of us are willing to point out the more discreet and inconspicuous folks in our midsts? People like my former bosses, who would never consider themselves to be racist and most certainly not white supremacists, despite their biased beliefs. How many of us are willing to call out the workplace culture that sympathizes with bias and systematizes how or which people of color are allowed to show up?

“Racism without racists,” Bonilla-Silva calls it. More aptly, it is white supremacy without white supremacists. And allyship without allies.

White supremacy is so prevalent in the workplace that major television networks have started producing shows about it. In HBO’s new series, Insecure, show creator Issa Rae uses humor to unpack the tense moment between a Black new-hire and white executive. In the episode titled “Racist as F*ck,” a character named Rashida is fired for portraying qualities that were deemed too Black for the law firm’s white-dominant culture. Through Rashida’s early appearances in the episode, we find she has an exuberant personality. Her laughter fills the hallway as she exchanges playful banter with her colleagues. But those same qualities seen through the gaze of Rashida’s white supervisor are seen as abrasive, loud and sarcastic – undesirable. Despite Rashida performing her duties well and to the satisfaction of her employers, her unwillingness to conform her identity to meet the company’s culture led to her swift termination.

In collusion with white supremacy is the system of wealth accumulation known as capitalism. In a capitalist society—where market need determines free trade—white supremacy inflates that need, controls trade, claims all of the spoils, then exercises its power to hide its hand. Capitalist white supremacy usurps opportunities to amass wealth and resources by exerting brute force. For centuries, white supremacy thrived on the enslavement of African labor, exploited Black, Latino, and Asian labor and the vast economies built on stolen Indigenous land. White supremacy is not having to acknowledge or pay restitution for committing any of that violence. In fact, white supremacy is the ability to reap future earnings because of it.

The audacity of a culture that opposes and oppresses people of color also patronizes with white saviorism and guilt. When whiteness witnesses racial inequality, it relies solely on its own will and ability to restore justice. Not only did my bosses selectively hire white volunteers at an organization serving 90 percent Black youth because they believed they were unlikely to find qualified volunteers of color, they also selectively hired white volunteers because white saviorism asserts that people of color can only be saved by whiteness. It is a circular and white-aggrandizing logic, but ultimately white supremacy creates the racial disadvantage that white saviorism responds to.

“The White Savior Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege,” tweeted author and historian Teju Cole. On a broad scale, white-led and white-dominant industries (e.g., education, social services, environmental affairs) believe their knowledge, strategies, and methods are superior to that of people of color. We see these paternalistic values in action every time a white-led organization partners with another white-led organization to be shepherds of funding, rather than giving directly to the populations they serve who are best equipped to direct funds as they see fit.

White saviorism and paternalism dictate what ideas are plausible, how funds are shared, and who leads. It creates a dynamic where marginalized peoples become pawns in a game of who can bring services to the largest number of people without engaging deeply and authentically with the folks most invested and impacted by their work. What’s tricky here is that white saviors believe they can dismantle white supremacy from a pedestal. If anything, their efforts only maintain their levels of power, privilege, and control.

Because we exist in a culture that elevates whiteness, white folks have mostly avoided having to deal with race-based stress in their careers. This avoidance builds a tolerance for racial comfort which means even the slightest amount of racial stress—like being called out for problematic language or being excluded from safe spaces reserved for people of color—becomes intolerable, triggering, and may prompt feelings of anger, cynicism, and defensiveness.

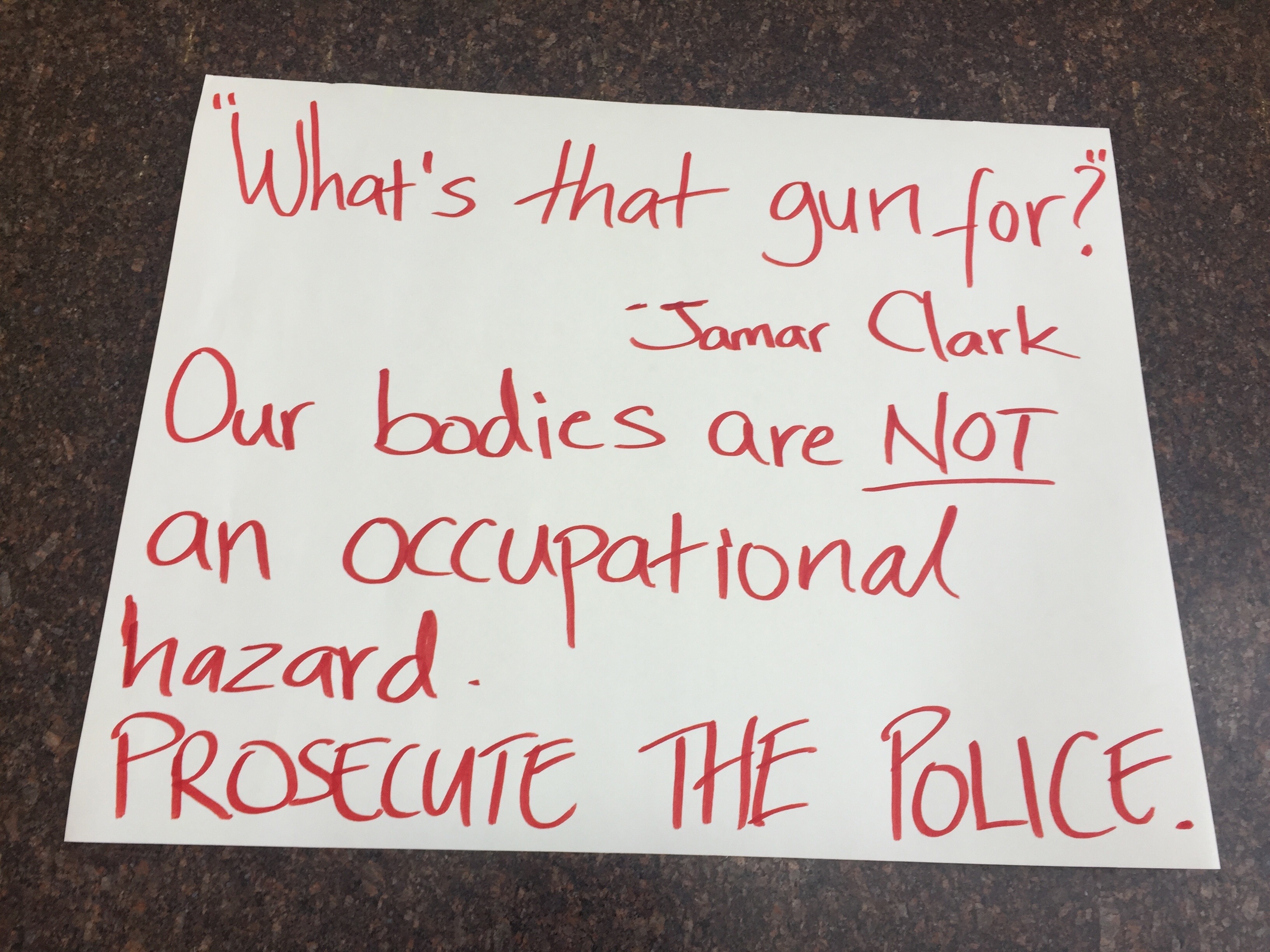

In order to build up that tolerance and create workplace cultures that can evolve, expand, and adapt to the multitude of people ebbing and flowing through them—in order for that change to happen—organizations must always be willing to critique and resist centering and elevating whiteness. This means not taking up space by loudly signaling allyship. It is pointless to hang “Muslims Are Welcome Here” signs from office windows and wear “Black Lives Matter” pins and t-shirts if your workspace doesn’t hire, promote, or retain people from those targeted communities. Dismantling white supremacy is not in the performance of allyship but in the humble approach to building lifelong equity, partnership, accountability, and trust with individuals from targeted communities, starting with the people in your workplace. If this doesn’t happen and toxic workplace cultures stay the same, the people of color working in these environments, by virtue of who they are and how they show up, are going to constantly and inadvertently become agitators against a system that will not make room for them.

The goal of creating an equitable workplace is not to center any one culture in particular, but to instead begin to challenge workplace norms and develop an adaptable and agreeable set of principles for everyone at your organization to exist in—not just the white folks. How can we create work environments that hold space for people while allowing constant change to also happen? We need to either say we want to uphold white supremacist work culture, or we can get real about where we are and what work we are trying to do.

If you have read this piece then I assume you want to do something to rid white supremacy from the workplace, your workplace. You know what the stakes are. Ask yourself honestly, what is stopping you from doing this work?

Join us on June 1 for rich discussion and to learn how you can build an organization around equity.

GET TICKETS

The Twin Cities Daily Planet is an award-winning, professionally-edited online publication that amplifies and connects marginalized voices. The Daily Planet is a media arts project of the Twin Cities Media Alliance, a nonprofit organization dedicated to equipping individuals and organizations with the power of media arts to shape narratives that advance equity and justice.

Contributors