Story Michael Kleber-Diggs

2020 Photos Sarah White 1960s Photos Phyllis Wheatley Community Center

Video Footage Historic Films

PRELUDE

Long Hot Summer

Minneapolis, early summer. An injustice perpetrated against the community by the police, followed by the community’s response. Protesters marching in the street, some of them dancing, some of them singing. As the sun set, voices demanding change were replaced by righteous rage – broken glass, incendiary devices, fires, businesses on fire. Where the injustice met with indifference in the broader community, the fires inspired concern. With the sunrise, while embers still ran hot, out from among crumbled structures came calls for calm. The Governor deployed the National Guard; they patrolled the streets for days “keeping the peace,” they said. “Restoring order.”

Minneapolis, Plymouth Avenue Riots, July, 1967

THE MESSENGER

(Then)

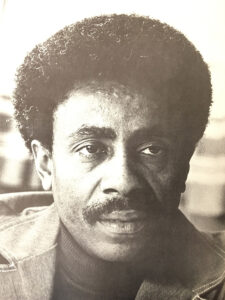

In the archives of Historic Films, there’s a 10-minute video of T Williams from 1972. Early in the video, T is behind the wheel of a sturdy American sedan, wearing large sunglasses, sporting a tall afro and a long mustache. He’s dressed in a navy sports coat, a white shirt with a gigantic collar, and spectacular, plaid pants.

Williams moved to Minnesota in January of 1965.

In October of that year, he became the Executive Director of the Phyllis Wheatley Community Center back when it was a settlement house, part of the settlement movement where volunteer workers shared knowledge and cultural concepts with community members, often with the goal of ending poverty. Today, Phyllis Wheatley focuses on youth education and adult empowerment. Williams speaks with carefully considered detail about his work at Phyllis Wheatley and the racial climate in the Twin Cities back then. 1965 was the year of the Watts Riots. In July of 1966, there was what Williams called “a disturbance” on Plymouth Avenue in North Minneapolis. The disturbance lasted about one day. In response, the Mayor of Minneapolis, Arthur Naftalin, and the Governor of Minnesota, Karl Rolvaag, actually met with residents in a park to ask what they wanted. The main answer was jobs.

The summer of 1967 was a long hot summer in America. There was more street violence than in any other year. All told, there were riots in 16 cities, including Minneapolis and Milwaukee, most notably in Detroit. In July of 1967, drawing back to a racially-motivated act of police violence during Juneteenth celebrations the previous month, and inspired by uprisings in other cities, young people in Minneapolis started to destroy businesses along Plymouth Avenue after the Aquatennial Torchlight Parade. “It lasted for about a day,” Williams said. “It did not get off Plymouth Avenue, the only property damage was along Plymouth Avenue. There was not any corresponding activity in South Minneapolis, things were relatively quiet over there.”

In 1971, there were riots in Attica Prison in western New York. In response to those riots, in July of 1972 Minnesota Governor Wendell Anderson used executive authority to create the first prison Ombudsman position in the continental United States. Williams was chosen to take on the role.

INTERLUDE

History Repeats Itself

Minneapolis, Late Spring. Worse this time. The ultimate injustice perpetrated against a member of our community by the police, followed by responses in several communities. Protesters marching in the street, some of them dancing, some of them singing. As the sun set, voices demanding change were replaced by righteous rage. People from outside of the Twin Cities, accelerationists, brought their own mayhem. Broken glass, incendiary devices, fire, police stations on fire, businesses on fire, two cities on fire, ten. Where police violence failed to inspire action in the broader community, the fires ignited concern. Some folks pointed their fingers at protesters. With the sunrise, while embers still ran hot, out from among crumbled structures came calls for calm. The Governor deployed the National Guard; they patrolled the streets for days “keeping the peace,” they said. “Restoring order.”

Minneapolis, George Floyd Uprisings, May and June, 2020

THE MESSENGER

(Now)

T Williams has a soft voice, and words come easily to him. He speaks in memoir. His ideas unfold gradually like essays on complex ideas. Williams’s career has been devoted to eradicating barriers and dismantling oppressive systems. He has an uncanny ability to recall names and dates from events that took place 50 years ago like they happened yesterday. T is history alive, an encyclopedia with a heart.

Today, Williams’s beard is mostly white. His hair is mostly white and shorter than it was in ‘72, a mini-fro. He wears eyeglasses, thick black frames setting atop functional if not fashionable nose pads. When we spoke, Williams was dressed in a navy-blue plaid short-sleeve button down shirt, and, from time to time when he lifted his arms, they appeared corded and reliable like well-made ropes. Mind sharp, body sharp, ideas keen. T is 81 going on about 61.

Williams has a message to share. Lessons learned in 1967 that, unfortunately, we still need to learn today.

MESSAGE

Comparing 1967 to 2020, T Williams says “what was characteristically different then from now is what was happening in the federal government. Lyndon Johnson convened a group of leaders in Washington. Top government officials, corporate leaders, civic leaders, religious leaders. Johnson addressed the group and asked them to go back to their communities and form urban coalitions focused on race and poverty. Forty or fifty people went to Washington from the Twin Cities.”

Back then, the corporate community took the lead instead of the government.

Williams pointed out that in the 1960s, even large businesses were owned by people who lived here. John Cowles, Jr., whose family owned the Star and Tribune newspapers, “convened a group of 14 corporate leaders from Honeywell, General Mills, Pillsbury, two major banks, the utilities, the Daytons and other highly-respected members of the community like Atherton Bean.”

Williams met Cowles at the urging of an influential Northside settlement leader named Larry Harris. Harris felt Williams would be an ideal partner for engaging the community in the work of reform. Williams described Cowles as quiet and soft spoken. Cowles asked to meet with Williams, and Williams said Cowles mostly listened but asked insightful questions. At one point, Cowles suggested that Minnesotans were mostly good and there was no racism here. Williams replied that “Minneapolis was living a lie.”

Concerned about the optics of 14 wealthy white men deciding how the city should respond to racial and economic injustice, Williams and Harris persuaded Cowles to create a forum comprising 60 people. The group included corporate, nonprofit, religious, and public-sector leaders, as well as members of the community.

“You’d have up to 40, 50 and sometimes 100 people in the room trying to conduct business,” Williams said. “People sat next to people who, under any other circumstances they would never be seated next to, and they’d start their own conversations.”

As one example, a conversation among Clyde Bellecourt, Dennis Banks, and Peter Dorsey led to the formation of the Legal Rights Center, designed to focus on Blacks and Native Americans in the criminal court system.

“There was a community response that led to specific community capacity building,” Williams says. “There was a place to take the gripes. The Urban Coalition was there. What couldn’t be cracked then and still isn’t cracked is the situation with the police, but the Urban Coalition had enough corporate diversity and connection with policy makers that they could put tasks on someone’s plate and monitor the progress. Today, we don’t have the kind of place where people can say ‘these are the things that should be happening and who’s working on it?’”

“We had public partners at that time, the state, the county, the city, and the feds. There is no federal partner now. When the Urban Coalition was established, we had the Vice President, Hubert Humphrey. Later on, we had Walter Mondale as a senator. There were far more federal resources then than there are now to address the kind of issues we’re talking about, there were more issues then than there are now, and the leadership was a better form of leadership.”

“Over fifty years have passed since the founding of the Urban Coalition.” Williams said. It helped business and other leaders learn first-hand what it was like to be Black and poor in the Twin Cities. This changed corporate, religious, and nonprofit organizations, and, in turn, the community.

Williams calls it the Urban Coalition Model. It was initiated by federal leadership, initially led by corporate executives, advanced by community leaders, and fulfilled by a coalition of clergy, non-profit leaders, and concerned citizens. As a result of this leadership forum, the Twin Cities created the Urban Coalition, a way to promote dialogue and advance advocacy around issues of race and poverty. The Urban Coalition became the go-to organization during times of unrest.

Corporate and non-profit leaders were transformed by their participation in the forum. After meeting with community members representing multiple races and cultural traditions, executives returned to their corporations and noticed their organizations were entirely white. “Their experiences during their time with the Urban Coalition had positive effects on their leadership, both within their corporations and the institutions in which they held leadership positions.” Those leaders went on to review “hiring and promotional practices and the vendors with whom they did business,” Williams said, concluding “if we can change individual behavior, those changed individuals will go into their different groups and begin to make a difference.”

POSTLUDE

Tomorrow

Minneapolis, early summer. People attend Juneteenth or the Aquatennial Torchlight Parade. They dance and sing in the street. As the sun sets, everyone goes home. Everyone makes it home. Everyone has enough to live. Everyone feels safe, protected and served by their government. As the sun rises, businesses open, just like they did the day before.

Riots and unrest are symptoms of a larger illness. They present opportunities to listen, to change, to improve. T Williams says our chances of creating a community where everyone is protected and served are improved if we have leadership at all levels of government, if we have public partners at the city, county, state, and federal level, if we have investment, financial and otherwise, at the federal level, if corporations and non-profits and churches are involved, if we sit next to people we don’t usually sit next to and start conversations, even difficult conversations. Our chances are improved if there is a community response that leads to specific capacity building, toward the creation of a place where the community can go if there are times of unrest.

In other words, we can build the future together. T Williams has ideas on how we build a better future. His ideas are informed by the past and the present.

We should listen.

Contributors