Words by Holly Harrison // Design by Tanner Groehler

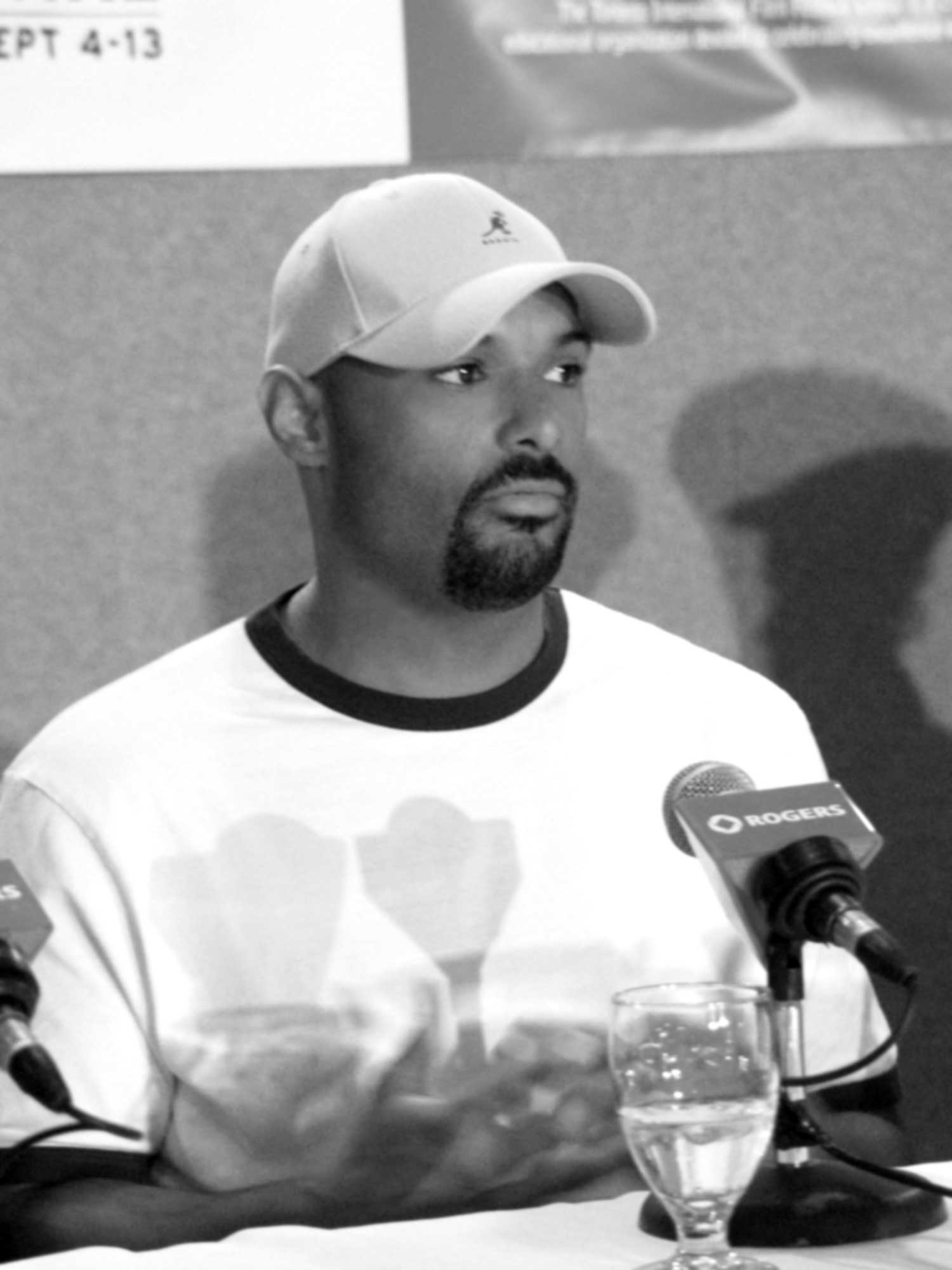

Michael Walker didn’t want to be the director of the Office of Black Male Student Achievement with Minneapolis Public Schools. At least, not at first. He’d already gotten his dream job.

“When I was [working for AchieveMpls], I saw this amazing assistant principal named Vernon Rowe, and I was like, ‘I wanna do what that guy does.’ He had the respect of teachers, he had the respect of students, and he had the respect of the community. So I sat down and had a conversation with him about how you go about becoming an assistant principal.”

AchieveMpls doesn’t just promote higher education for students; they also promote it for their staff. Michael was able to get his principal license with AchieveMpls’ support and then became an assistant principal at Roosevelt High School, the very high school he’d graduated from years earlier.

So when he was approached to be the Office of Black Male Student Achievement’s director, he almost said no. “I enjoy working directly with the young folks. I didn’t want to be in the front of a space where I knew there was going to be a lot of media attention and scrutiny.”

“You always have that one person in your life who can just explain things to you in a certain way where you can’t really say no. That person is my mother. So before I made this decision to say no, she just outlined my life for me. She said, ‘OK, Michael. When you were at the YMCA, you wanted specific programming for black males. Remember when you had those thirteen young black men that you worked with four summers in a row, taking them to visit companies, taking them camping, playing sports with them, feeding them nutrition? Then you took on the role at AchieveMpls, remember how you would set up specific opportunities for colleges to come meet with black males, letting them hear about certain scholarships and taking them on college visits? Remember when you were assistant principal and you created a young black men’s group in your school to support the black males in your community and make sure they had the space they needed to develop?’

“She said, ‘You’ve been doing this all your life. You need to accept this position and step out there and show people what you’ve been doing all this time and how you’ve impacted people’s lives.’ When she said that, I was like, ‘You’re right.'”

It’s been a year since Michael kicked things off with the Office of Black Male Student Achievement, only the second program of its kind in the country. He sat down with us to talk about what he’s learned so far.

So first, explain what you do.

Our office is focusing on three bucket areas that we came up with from our listening sessions last year. We’re focusing on professional development for educators, authentically engaging our families and communities, and then direct service with our teens.

Sometimes I get the question: Why do you name the kids last? My thought is it’s about adults. What are we doing to support our young men? What are we doing to support our young students? Depending on how we act or how we behave, that’s the reflection we get from our young people.

It’s a lot to expect of young people, to ask them to just throw off stereotypes and expectations that have been built up for them for centuries.

Exactly. Exactly. I guess that’s kind of what we do. We provide professional development for schools, for different departments in our district.

When I say, ‘authentically engage with families and communities’ it’s about how we go out of our own way sometimes. We expect families and parents to come to our buildings versus getting out to their spaces. I always tell people to think back—data about students of color not performing well academically is not really new, right? We know that our suspension rates for black males have always been high and out of whack, right?

So why do we think that our parents didn’t have that same experience going through our school system? I don’t claim to be an expert on trauma, but I know if I had a traumatic experience in a space, I’m not going to want to go back there. So we have to rebuild trust with our families to encourage them to come back into the school setting. In order to do that, we have to get out of our comfort zones and go to their spaces. We’re connecting with community-based organizations who have already gained that trust with families and seeing if we can partner with them to build on what they already have. We’re listening to their concerns and trying to implement that into our school system.

Everything you’ve just heard me share has our students at the center. They’re at the table with everything we do. So we’ve designed a class for them called B.L.A.C.K. (Building Lives and Acquiring Cultural Knowledge). We’re piloting that class in four high schools and four middle schools. They’re learning about who they are. It’s not a typical class. Classes are usually linear. you start from 1920, you go to 1970. This class centers on the young person. It looks into the future, into the past, and shows how that impacts how the students relate to the world and how the world relates to them. There’s some history that goes on in that class, there’s some self-identity and self-worth pieces, character development, and then there’s also just curiosity. What do they want to learn? It’s about the black male experience.

What have you learned after a year of the program? What has been most rewarding part of your work?

The most rewarding is always just seeing the young people, right? This summer I hired five STEP-UP interns this summer to work in the office—five black men. I learned so much from them and hopefully they learned a lot from me. Again, their voice was present at every single step of what we did. I had them as my advisors, and right now they’re basically the majority of my advisory board. I bring them to meetings with me when I’m with other adults and let them share their experience.

It’s all about them, as I tell folks. I’m not sharing Michael Walker’s experience. People need to hear the perspective of the young men in the school district right now. They need to know their voices matter. People can discredit me all day long, right? But you cannot discredit the voice of this 16-year-old or 12-year-old young man.

I imagine you get a certain amount of opposition to the idea of “singling out” young black males. How do you explain your office to people who don’t get it?

When you go to the doctor, you get your general check-up. And sometimes they may find something wrong with, say, your elbow. So they send you to a specialist to tell you about your elbow, tell you how to rehab it and all that stuff. That’s what’s going on with our young black men right now—not necessarily that they need a specialist, but our system needs a specialist to learn how to work with and support young black men. That’s our role as the office.

I hate to share data, because it’s all negative and everyone knows that. But young black men are either the lowest or next-to-lowest on every academic success scale nationwide. How can you say that that doesn’t need extra attention?

Now, are there other groups that need extra attention as well? Yes, for sure. But the work that we do with our black males can be the catapult for other marginalized groups we want to work with. If these things work with young black males, we can transfer that into black females or Latino males, Latino females, Native American students, right? Hopefully it’ll expand. But we have to start somewhere and be laser focused.

Your work centers on belief and how changing people’s beliefs changes systems for the better. This is kind of mushy, but how have your beliefs changed in the past year?

Going into this role I didn’t know how much professional development was going to be part of it. That’s not something that I was interested in at all. Of course as an adult you go to professional development you learn some things and you go back and implement it here and there. But I never thought I’d be the person delivering professional development for large numbers of school district employees and educators. My beliefs have changed to see that professional development is an initial start to help people self-reflect and give them tools to utilize in our classroom with young black males. At first I wasn’t so strong on professional development, but now I see that it can have an impact and it can be coupled with actual hands-on work with the young people.

For the rest of the work, I don’t think my beliefs have changed much. I know that our young men will be successful. I know they already are successful. One thing that I stress is that our office is not here to “save” anyone. These young men have greatness already within them. Our job is to help them develop it and pull it out.

You mentioned working with different audiences: with students, with educators, with parents, and with the community in general. What’s the biggest misconception about any of these groups that needs to be changed?

The parent group. We have preconceived notions about parents and whether they’re supportive of education because they may not show up for parent/teacher conferences, or they may not come to different events. We think that they’re not committed to their kids’ education because we don’t necessarily see their faces. And I think that’s a big misconception.

You’ve got to understand that folks have different lives and responsibilities. When we look at our families and we say, “Well, they’re not showing up at parent/teacher conferences”—well, maybe they have to work. Maybe they have kids in different schools and can’t catch a bus to go to all the conferences and have to prioritize. That doesn’t mean that they’re not coming home and checking in with their kids. We have to understand that. These kids are their babies. Of course they want their kids to be educated. Of course they want them to be successful.

Let’s not use that as an excuse. We’ve gotta figure out how to be more receptive to parents. How do we work within their schedule? Everything is predicated on our schedule as educators. Maybe a weekend is better for the parents. Y’know? Maybe I don’t have transportation to get in, so maybe it should be a phone call. We have all this technology—why can’t we FaceTime for parent/teacher conferences these days? Who said that’s against the rules? We have to figure out how to be more creative around connecting with their families.

There’s also the misconception that our young men are not interested in learning, or that they can’t learn, or that they’re not connected to schools. I have kids running to their B.L.A.C.K. classes. They want to learn. They want to feel valued. They want to feel like they have a voice. They want to feel like they can make mistakes without being criminalized. They just wanna be kids like anybody else. And that’s what they are —kids like anybody else. But they’re not seen that way too often. That’s why there’s a disproportionality of suspension rates with our black males—we view them as criminals.

What would your office look like if it was operating at full capacity?

It wouldn’t be an office. It would be a school.

We’d have a school—and I’m not promoting segregation or anything like that—but a school for black males with black men as their teachers. There would be reading, writing, and arithmetic, but they would also learn the true history about themselves, about all the good that came before we arrived on this continent in 1619. We’d work on their self-identity and self-worth.

We’d have a school with teachers that look like our students. That support our students. It’s not that I think only black males can teach black men. The most important thing is having a master teaching that classroom. That can be a white female, or a Native American teacher—I want a master teacher in that classroom who is culturally responsive, who understands who’s in front of them and how to make the curriculum relevant.

Part of their school day would be them out on job sites at professional buildings so they can understand all the different jobs and different opportunities out there for them. You only know what you know, right?

The reason it sticks with me is that when I first moved to Minnesota from Gary, Indiana, when I went downtown for the first time, I was like, “What’s in all these tall buildings?” I didn’t find that out until I was 19 or 20 years old. Originally I wanted to be an accountant, even though I’d never met an accountant—just because I took that class and got kind of interested. I didn’t even really know what an accountant did. I just knew they messed with numbers. But if I’d had some information earlier at age 11, 12, 13—maybe I would’ve realized I wanted a different career. So how do we put that in front of our students?

You’ve been interviewed a lot. If you were in the interviewer seat, what’s a question you’d like answered?

I wish I could ask people this question: What is their real belief around black males? That’s the question that is at the center of all this. Do you believe that young black males can be successful? Do you think that black men are pre-conditioned to be criminals?

If you can get to the truth with that question, then you can move forward. It’s about self-reflection. They wouldn’t have to answer it to me out loud. But I want them to answer it to themselves. Like, what do you really truly believe? And then once you know it, it’s ok if you don’t believe black males can succeed. At least now we can work on changing that.